No one can be here long without feeling burdened by history. Over the last century, Vilnius’ national identity changed half a dozen times, with control passing among Russia, Poland, Germany and the Soviet Union as well Lithuania, which won and lost its independence several times. In the process, hundreds of thousands of people were slaughtered, exiled and/or suppressed for cultural or political reasons.

That said, the city has produced more than its share of writers, artists, musicians and institution-builders, across its ethnic and religious spectrum. Names and busts of such people as Romain Gary, Jasha Haifetz, and Adam Mickiewicz show up on buildings marking their former homes. It’s not even the largest city in the Baltics (that would be Riga, in neighboring Latvia) but Vilnius has an outsize place in history.

That goes double or triple for Jewish history. Until the Nazis wiped it out, the Jewish community of Vilna was preeminent, known for its scholarship and enterprise. It was the capital of the Litvaks – Jews who settled from the 15th century in what was once the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and who, by the 20th century, had founded or overseen pretty much all of the world’s most important Jewish institutions, from the pastrami sandwich to the Hebrew University.

I say that as at least a five-eighths Litvak, but it’s not just me bragging. A Philadelphia rabbi I know named Bob Tabak once wrote an academic paper in which he made the same case by analyzing U.S. immigration records by city of arrival. The communities that produced the most dynamic and important Jewish institutions – religious and secular both – were those with the highest share of Litvak immigrants, he claimed.

It’s also objectively true that Litvaks comprise the overwhelming majority of the Jews of South Africa, who have been active in all facets of that country’s dramatic history since 1900.

But back to Vilna. I took a walk this morning past the neighborhood that once was the city’s Jewish heart. The Great Synagogue of Vilna was here, along with numerous smaller prayer houses and libraries that by the 1930s held tens of thousands of precious books and records dating back to the 1500s. The area had been known as a center for Jewish learning since then, but it became particularly revered during the time of a rabbi named Eliyahu, whose vast learning and erudition earned him the nickname “Gaon” or genius. Today the Vilna Gaon’s former residence is marked by a rather odd statue:

After 1941 the Germans turned the area into a locked ghetto, looted the books and murdered most of the inhabitants in a nearby forest area called Ponar. When the Red Army retook Vilna, the neighborhood was a shell; the Soviets ultimately razed what was left. Today it’s a small, disheveled park with a childrens’ playground.

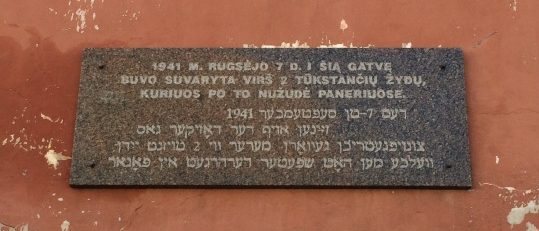

Nearby, on a wall, a plaque recalls what happened here. The inscription, in LIthuanian and Yiddish, says “On September 7, 1941 in this street, more than 2,000 Jews were driven together, who later were killed in Ponar.”

Leave a comment