Here’s what I’ve been up to:

As a young man, my grandfather had a friend named Aharon Pick. The two of them collaborated on a project to collect Yiddish folksongs in and around their hometown, Keidan, in Lithuania. My grandfather emigrated to the U.S. in 1904; Aharon Pick went to France, where he graduated from medical school. After World War I he moved back to Lithuania, to the city of Šiauliai, and became one of that town’s leading physicians. He was active in civic affairs and public health, leading vaccination efforts and other projects.

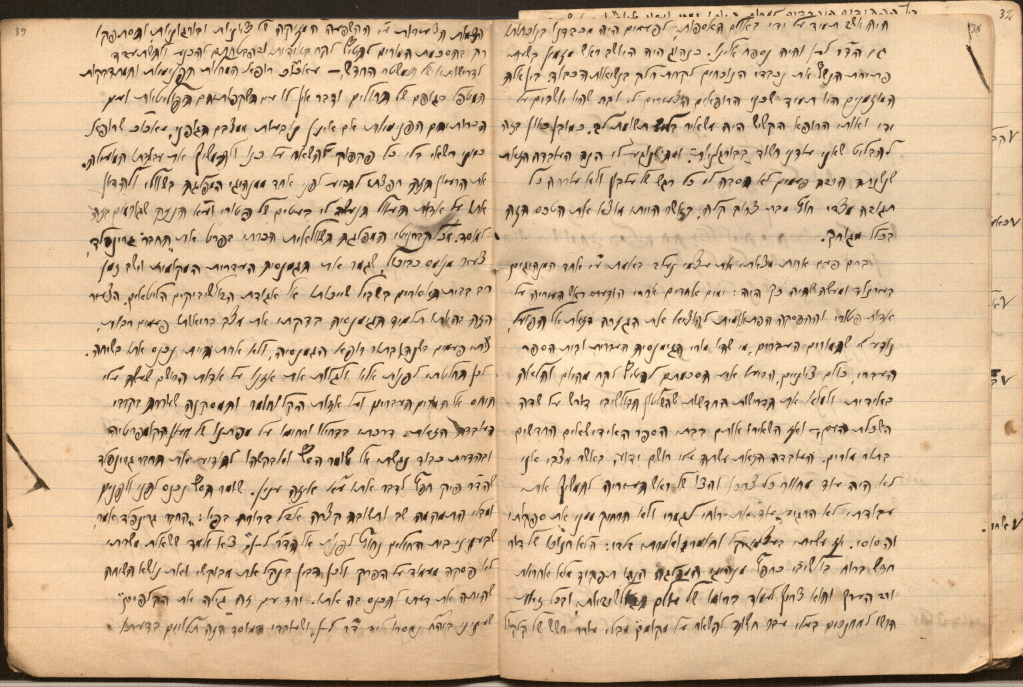

When the Nazis occupied Lithuania in 1941, Pick and the other Jews of Šiauliai (those who were not immediately murdered) were forced into a ghetto. He recorded his experiences there in a diary, which he kept until his death in the ghetto in 1944. Written in Hebrew, the diary was preserved and taken to Israel, where it was published in the 1990s.

A couple of years ago, I heard that the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington had acquired Pick’s original diary. This year, I also learned that someone had volunteered to translate all 300-odd pages of it into English. I contacted that someone — a retired professor from the University of Virginia named Gabriel Laufer — who told me he hoped to publish his translation, but that it needed polishing. I volunteered.

It is a difficult text, for several reasons. The first is that Pick wrote an archaic style of Hebrew, one that predates the language’s modern revival. It’s full of references to the Bible and Talmud, and uses terms that modern Hebrew has abandoned. Germans, for example, are referred to as “Ashkenazim” — from the ancient name that we now associate with European Jews, but which first simply denoted the lands of central Europe.

Pick’s cadence and sentence structure, moreover, derive from the medieval rabbinic commentaries he read as a boy in yeshiva. Conveying all this, while still making his observations and reflections clear to a contemporary reader of English, is just as challenging as you might imagine. It’s even more complicated because we – Laufer and I – are doing this as a team. He’s a native speaker of modern Hebrew who taught engineering in the U.S. I’m a retired journalist and editor with a rudimentary (at best) knowledge of Hebrew.

I believe it’s worth trying, though, and hopefully not just because of my personal connection to the author. As Laufer wrote in his draft introduction:

The authentic account of his life as the world was closing on him, his family and his community are heart-wrenching. But his resilience, his never-ending hope to survive, and his determination to immigrate to Eretz Israel after the war, are inspiring. The diary demonstrates that Holocaust victims were not “sheep led to slaughter”, but rather lions caught in terrible circumstances.

We hope that at the end of this process the translation can be published in book form. I also hope it can be put on line, preferably by the Holocaust Museum as an adjunct to the original manuscript (which is accessible at the museum’s website already). If we are successful, we will have a document that should be of interest to anyone studying the Holocaust, particularly as it happened in Lithuania.

Anyway, that’s what I’ve been up to.