The Philadelphia Inquirer, THURSDAY June 8, 1989

By Andrew Cassel, Inquirer Staff Writer

SPRING GREEN, Wis. – One warm June evening here a few years ago, Richard and Bernice Smith stood before Frank Lloyd Wright’s grave, telling him about their house.

It had been one of the master architect’s later designs, an example of his “organic” building principles at work. In architecture circles and in their home town of Jefferson, about 65 miles east of here, it was famous. Students and historians dropped by frequently to study it. Magazine photographers took pictures.

But the Smiths weren’t there to say thanks.

“The bathrooms were inadequate. The closets were inadequate. The bedrooms were terribly small,” Richard Smith recalled. “The first winter we were in there we pretty near all froze to death.

“You could never air-condition it, and it was so humid that all the books mildewed. . . . I can still smell that pungent smell. And the kids could never bring their friends to that damn house. It just didn’t lend itself to anything.”

When the house was new, Smith had tried complaining to a very-much-alive Wright, telling him for example that the concrete slab on which it sat got cold during Wisconsin winters.

“I said, ‘Mr. Wright,’- I called him Mr. Wright. He called me Smith – ‘This is a nice house, but it’s totally impractical.’ He said, ‘Smith, you can’t have both beauty and practicality.’ “

“I said, ‘Mr. Wright … this is a nice house, but it’s totally impractical.’ He said, ‘Smith, you can’t have both beauty and practicality.’”

Twenty-five years and thousands of dollars in repairs later, Smith and his wife stood in the Wright family graveyard, just down the valley from Wright’s own famous house, Taliesin, and bluntly explained why they were finally selling out.

“My wife did an oration, a harangue actually, and told the old man all the things she didn’t like,” Smith said. “We didn’t get any response from the old gentleman, but then he always was terribly difficult to deal with.”

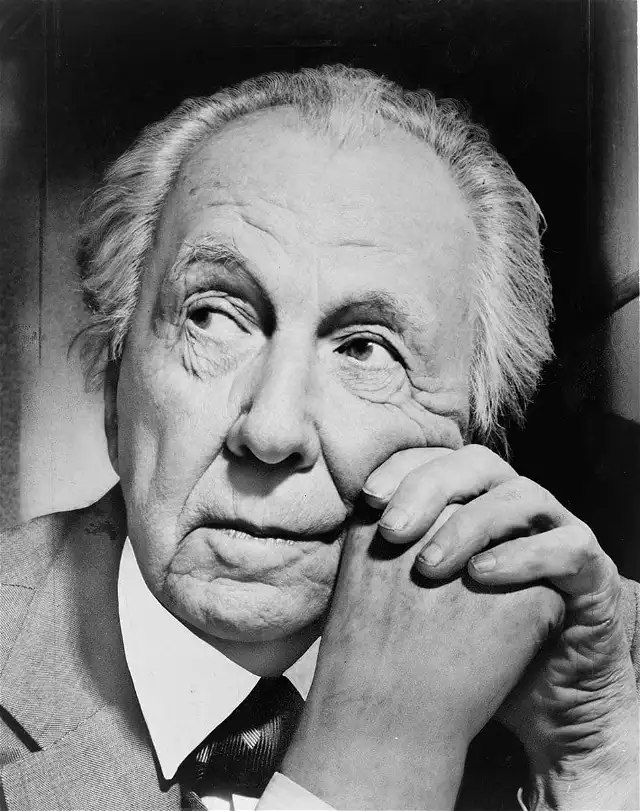

A lot of people here think of Frank Lloyd Wright that way. For decades, the man considered America’s greatest architect alternately graced and insulted, enthralled and repelled his neighbors until his name was almost an invitation to battle.

Thirty years after his death – and precisely 120 years after his birth on June 8, 1869 – Wright is the height of international fashion. A single small table he designed sold recently for $175,000 at Sotheby’s auction house. But here in southern Wisconsin, eyes still roll, and stories are whispered about his out-of-wedlock liaisons, his unpaid bills, his grandiose pronouncements on everything from war to zoning.

And though the man’s remains were removed to Arizona four years ago at his widow’s posthumous request – a final insult, many locals felt – Wright’s contentious spirit is once again threatening to haunt the lush green valley where he grew up, settled and built what some argue was his greatest residential structure, Taliesin.

“Here We Go Again,” proclaimed the Wisconsin State Journal last month, about a plan to revive a 96-year-old Wright design for a boathouse in the city of Madison. The proposed 100-foot-tall structure, to be built on one of the Wisconsin capital’s two adjacent lakes, has revived memories there of a bitter, 30-year battle over a mammoth civic center Wright wanted to build in the city he considered his home town.

Meanwhile, a subtle struggle is taking shape over the future of Taliesin, Wright’s name for the sprawling home he built and rebuilt over 50 years on the brow of a hill near Spring Green.

Age, weather and Wright’s own building methods have caused the buildings to age rapidly. The commune of disciples he left behind has been unable to keep it up, despite their ownership of an estate valued in the tens of millions.

State officials, including Wisconsin’s governor, would like to step in, renovate the property and use it to promote local business and tourism. But they must overcome expected resistance by both Wright’s former apprentices and the Wisconsin electorate, which has historically balked at spending tax dollars on anything connected with Wright.

“Just the other day I was at a party, and a doctor’s wife said to me, ‘I wouldn’t give you anything for that scoundrel,’ “ said Marshal Erdman, a Madison architect-developer who worked with Wright during his last years. “Most people he scared, but it’s hard to describe what a genius he was. . . . He was ahead of his time in everything you can think of.”

At Erdman’s urging, Wisconsin Gov. Tommy Thompson last year formed a commission to study restoration of the 600-acre Taliesin complex, which dominates a section of the Wisconsin River valley 45 miles west of Madison. Like many in the state’s current business-minded political establishment, Erdman sees Taliesin as a state treasure that has been grossly underappreciated.

“Last month, the governor went to Switzerland. When he tried to sell cheese, instead of people asking about cheese they asked him about Frank Lloyd Wright,” Erdman said.

Erdman envisions executive conferences, political gatherings and tens of thousands of tourists filling Wright’s buildings, buildings that now are unused much of the year. He points to Illinois, where the state government has spent heavily to restore a single Wright-built home near the capital of Springfield. “For the state of Wisconsin not to do a thing like this is pure stupidity,” he said.

Since the late 1930s, members of the commune-like architecture school Wright founded have migrated each year between the grounds here and a winter home in Arizona called Taliesin West. From June to October, tourists are admitted to part of the school complex, but Wright’s own house and studio are off-limits except to a handful of scholars and invited guests.

What those privileged few see is both marvelous and distressing. Wright played with ideas constantly at Taliesin, adding and rebuilding as his style and vision changed. “There was a house that hill might marry and live happily with ever after,” Wright wrote in his autobiography. “I fully intended to find it.”

Named for a mythic Welsh poet whose name means “shining brow,” the house emerges from the brow of its hill, commanding wide views of the valley. Inside its semi-enclosed courtyards, living rooms and passages are stunning examples both of Wright’s inventive mind and of his passion for collecting fine Asian art.

But throughout the building, plaster is cracked, stone is loose and wood is worn rough with age. An elaborate Japanese screen above his studio is rotting. Original pieces of Wright furniture, like those that have sold recently for five and six figures, are chipped and stained.

Heating systems are ancient and insulation nonexistent, moreover, making the house uninhabitable in winter. Worse, there is no sprinkler system, and much of the electrical wiring is outdated. Fire is a continual worry; just last month, a gas leak sparked a blaze that damaged one of the outlying buildings.

Members of the Taliesin Fellowship, who double as faculty in the school and directors of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, which owns the property, say they have been diligent in keeping up the property, which for many of them is home half the year.

“It’s a gigantic estate,” said Richard Carney, managing trustee of the foundation. “We have not had enough money to do a good job of rebuilding, but to say that the buildings are on the verge of collapse is not correct. . . . The buildings are actually in better shape now than they were when Mr. Wright died.”

Wright built on a shoestring, usually strapped for cash despite his fame, and ended up using cheap materials and unskilled labor. He was also often oblivious to existing technology, designing structures that seemed to call for methods and systems not yet invented.

Building Taliesin from the ground up today would be considerably cheaper than restoring the original building, which is expected to cost about $14.7 million, according to Erdman.

The situation has grown more ironic as the market value of original Wright objects has soared in recent years because the foundation itself owns what is certainly the largest collection of his papers, furniture and glasswork in the world. In the archives at Taliesin West are 23,000 original drawings and 200,000 documents and manuscripts, and the two Taliesins hold what may be one of the largest collections of Asian art in the country, Carney said.

Charles Montooth, who has lived here since he was a Wright apprentice in the 1940s, said some members have suggested – in jest – selling a few original pieces, replacing them with copies and using the profits for restoration. “We kid among ourselves,” he said.

But Erdman said Taliesin’s predicament is no joke. “They are struggling,” he said of the fellowship members. “They are having a fight among themselves.”

At issue specifically is a state proposal to transfer ownership of Taliesin to a new organization, whose board of directors would be stacked in favor of non-fellowship members. Although members of the fellowship generally support some restructuring, the group is reluctant to cede control of the property, according to Erdman.

“That’s a hard thing for them to give up because it’s their home,” Erdman said. In addition, the state plan calls for opening up Taliesin to tourists, and projects that up to 200,000 people a year might visit, something that could dramatically change the atmosphere on what has historically been a bucolic, retreat-like campus.

But even if the state wins full cooperation from Wright’s former disciples, there remains the problem of raising money in a state where Wright’s name is still legend for reasons other than architecture. “He didn’t pay a lot of bills,” said Nicholas Muller, head of the Wisconsin State Historical Society.

When Wright moved back to Spring Green, near his birthplace, from Oak Park, Ill., in 1911, leaving behind his wife and children for another woman, his neighbors asked the sheriff to evict him. During World War II, he angered war-effort groups by arranging agricultural deferments for his apprentices, who farmed the Taliesin grounds part time. His relationship with the community remained equally tenuous through his several marriages and affairs and was not helped by his penchant for sounding off in public.

“He enjoyed needling people,” recalled Carroll Metzner, a Madison lawyer who fought for years against Wright’s civic-center plan there. “He used to call us a one-horse town – this while we were supposed to be considering his project.

“We had a debate once, he and I. He finished speaking, then I got up, and as I was talking, I got heckled. After a minute, I realized it was Wright, heckling me from behind. I turned around and said if he wasn’t through, he could come back and continue speaking. . . .

“It was after we defeated the project that he said publicly I should be assassinated.”

Any state proposal to finance Taliesin’s restoration will be controversial, Metzner predicted. “I think the public will be outraged if they use any tax money to revive the thing,” he said. “For a lot of people, it still carries a lot of bad memories.”

But Erdman is hopeful that those memories are sufficiently dim, at last, to allow some state aid. “I am surprised at how well accepted (the Taliesin project) is,” he said. “I’ve had people call me to offer support who 15 or 20 years ago wouldn’t have dreamed of supporting Mr. Wright.”